1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has accelerated a paradigm shift in the manner by which schools offer and facilitate learning, including STEM education. Within a K-12 setting, AI-powered tools are capable of providing personalized learning, immediate feedback, as well as guided explorations, which traditional learning aids are hard-pressed to achieve (Kavitha & Joshith, 2024; Z. Liu et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2025). Other systematic reviews identify the importance of the mentioned adaptive programs in dealing with difficulties faced by computer science and physics educators, including a lack of teaching experience and the abstract foundational principles, by providing dynamic and personalized scaffolding and real-time analytics (Al-Kamzari & Alias, 2025; Z. Liu et al., 2024). Within the UAE, and with their priorities centered around digitization, future readiness, and smart learning, the inclusion of AI supports the UAE Ministerial Agenda related to smart learning and AI knowledge skills (Yehya et al., 2025).

The applications in physics learning could significantly benefit from the strength given by the characteristics mentioned. The notions presented by mathematical precision and their properties could be better explained by hints, simulation, and dialogic feedback (Kotsis, 2024; Sung et al., 2024). Nevertheless, as has been highlighted, an important issue, a crucial condition given by the literature, regards teachers’ readiness, their respective roles, evaluation approaches, and ethics/privacy concerns (Al-Kamzari & Alias, 2025; Bergdahl & Sjöberg, 2025; Dewi PURBA et al., 2025).

This study makes an empirical contribution with findings drawn from a UAE classroom. We examine whether AI-based instruction enhances Grade 11 Advanced Physics outcomes better than traditional teacher-led instruction. Based on the gathered data and findings, this study will present a large effect size (using Cohen’s d statistic = 1.21) in favor of the AI condition. We will proceed to discuss our findings by synthesizing the present body of evidence emerging from systematic reviews, and make suggestions informed by findings, focusing on the customized delivery of instruction and assessment approaches suitable for a secondary school physics program operating in a Gulf country like the UAE. The significance and aim of this study are designed to examine the effectiveness of AI-based instruction, as opposed to traditional teacher-led instruction, to better enhance Grade 11 Advanced Physics outcomes within a UAE Applied Technology School, henceforth termed as an ATS school. Specifically, this study was developed around 3 research questions:

-

RQ1. Does AI-assisted instruction lead to significantly higher post-test achievement in Physics compared to traditional instruction?

-

RQ2. What is the magnitude of the difference in student achievement between the AI-assisted and traditional groups (effect size)?

-

RQ3. How does AI-assisted learning influence the distribution and consistency of student performance across the class?

2. Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

Our conceptual perspective views AI as a complementing pedagogical actor, strengthening but not replacing the central instruction role of the educator. We identify three strands of theory and evidence emerging in the reviewed literature that correspond to Liu, Z., et al.'s (2024) PRISMA-guided synthesis regarding the dual role of AI as both subject matter and delivery channel, as well as to that of Torralba (n.d.) and Dewi Purba et al.'s (2025) conceptual perspective regarding ‘scaffolding ecology’ encompassing both human and system roles.

A. Personalization & Adaptive Feedback in STEM

Environments involving AI are useful due to their adaptability related to difficulty, pace, and representation, resulting in known gains relating to knowledge or skills, often through intelligent tutoring systems, or Teachable agents (Hu, 2024; Kavitha & Joshith, 2024; Xing et al., 2025). Such gains are often coupled with a boost in engagement or quality feedback, or better alignment between mistakes and their corresponding corrections (Sung et al., 2024).

B. Scaffolding, Inquiry, and Mentor Roles

Generative AI can play “mentor-like” roles, including teaching assistant, peer agent, or virtual mentor, providing explanation, hints, and metacognitive prompts that enable students to plan and regulate their learning activities by themselves (Castañeda et al., 2024; Dewi PURBA et al., 2025). The role is consistent with labels including “teaching agent” or “virtual mentor,” which appear even more crucial if the students are engaged in self-directed or out-of-class studying activities.

C. Teacher Capacity, Diffusion, and Responsible Integration

The process of adoption is, however, unequal, varying among teachers according to self-efficacy, professional development, resource availability, or perceived utility/entertainment value (Bergdahl & Sjöberg, 2025; Wattanakasiwich et al., 2025). The role of teachers as facilitators, assessor, or co-designers, as suggested by Torralba (n.d.), is a critical point to be addressed, also stressing Dewi Purba et al.'s (2025) argument related to AI-mediated instruction delivery: the necessity to define teaching roles (2025). The model by Rogers (2003) supports unequal diffusion at various stages, including, in order, knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation, related to physics education training, writing assistance, and assessment, as suggested by Elshall & Badir (2025) and Liu, Z., et al. (2024) respectively.

In Physics, all three areas come into play: conceptual learning involves iterative feedback and multiple representations, inquiry-based learning succeeds if students can try out ideas with immediate feedback, and teaching roles change toward orchestration, analytics, and ethics.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Syntheses and Reviews: State of the Field

There has been an emerging body of inquiry examining the educational potential of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools within K-12 STEM education, although the findings are varied by subject matter and grade level. The umbrella review done by Zhang et al. (2025), which aggregates thirteen other reviews published by subject matter, including science, mathematics, computer science, and integrated STEM, illustrates the continued preponderance of system development rather than integration, with a clear call by the authors for future quasi-experimental designs and improved articulation of implementation parameters.

Complementary bibliometric and systematic reviews by Kavitha and Joshith (2024) validate that AI-based intelligent learning tools, including robotics, chatbots, auto-scoring, and feedback systems, can positively contribute to engagement and conceptual understanding when incorporated as part of well-designed learning interventions. The results emphasize that the implementation quality and readiness of the institution are critical areas that are commonly underdeveloped in the K-12 levels. Liu, Z., et al. (2024) demonstrate, as well, that computer science education programs designed with an AI-based adaptive learning approach are capable of personalizing learning, decreasing teachers’ cognitive demands, and resulting in significantly augmented engagement and learning among students. The identified challenges, as highlighted by the authors, include small sample sizes, a lack of theory, and ethics/data concerns, respectively.

Moore et al. (2022) foster this critique by pointing out that intelligent systems have, to a large extent, been tested either in mathematical or informal learning environments as opposed to actual classroom environments. As a result, a holistic approach toward evidence-based integration of AI exists, including its integration into physics lessons, particularly in countries like the UAE, which has a strong focus on innovation and transformation through education, as indicated by their curriculums related to future-proofing education. The current study directly addresses this gap by implementing AI-supported learning in an actual Grade 11 physics class at an Applied Technology School, which addresses the innovation-focused curriculum promoted by UAE education.

3.2. Physics-Specific Evidence and Roles for AI

Within the broader context of secondary physics education, studies are emerging to elucidate the role of AI-based applications to enhance conceptual understanding, experimentation, and motivational aspects as well. Based initially on the meta-analytical results presented by Hu (2024) and Liu, Z., et al. (2024) between adaptive personalization and substantial improvement in STEM areas, a systemic analysis by Al-Kamzari and Alias (2025) concentrates solely on using AI, initially yielding a consistent improvement at the conceptual levels among secondary students via adaptive approaches, intelligent teaching, and virtual labs, though facing difficulties regarding teachers’ readiness, privacy concerns, and the risk of dependency. Such a systemic analysis argues that training and organizational strategies are prerequisite requirements if AI is to make a lasting impression, as seen among UAE schools adopting AI technology under their smart learning program initiatives.

Such results are confirmed by empirical research. Henze et al. (2024) tested the effectiveness of AI-based data analysis support compared to traditional spreadsheet-based activities in pendulum tasks, observing a similar quantitative improvement, but a marked difference: greater intrinsic motivation, lower anxiety, and a greater degree of engagement emotionally. Such results nicely supplement the achievement profile of the present study by highlighting how cognitive and affects are intertwined as a regular occurrence when AI-based physics instruction is involved. The study by Kotsis (2024) illustrates once again how support via ChatGPT facilitates inquiry, analysis, and critical thinking skills via instant resolution and feedback, even in primary school activities involving hands-on experimentation. Perhaps due to the age difference, participants were primary school students, but the strategy of rapid feedback and diverse representation could well be applied to physics at a secondary school level, as the subjects require visualization and iterative explanations.

Instructional-wise, Wattanakasiwich et al. (2025) examine the acceptance of physics teachers toward Generative AI, applying a diffusion model proposed by Rogers and the UTAUT2 model. The results show that hedonic motivation, teachers’ beliefs that AI is fun and entertaining, is a stronger determinant than performance expectancy, although barriers like a lack of technical know-how and uncertainty about the accuracy of AI remain. Findings confirm the importance of professional training oriented toward teachers’ expertise, including expertise related to designing, validating, and understanding the limitations of AI, even as teachers are charged with the responsibility of incorporating AI effectively into their science curriculum delivery in the UAE.

3.3. Virtual Mentoring, Teachable Agents, and Inquiry

Aside from traditional tutoring roles, emerging literature highlights the potential role of AI as a mentor or collaboration partner for learning. Studies by Castañeda et al. (2024) explored the utilization of ChatGPT as a virtual mentor for K-12 science, yielding around 30% grade improvement and satisfaction rates among 70% of participants. The significance of providing constant, timeless support, as seen with the “always-on” feedback model provided by many AI-infused learning tools, is well represented by the mentioned contributions, as this current UAE study shares a similar structure providing adaptive support through guided activities.

Teachable agents, whereby learners consolidate their knowledge by teaching AI, offers a related strategy. Xing et al. (2025) created a “generative AI-based agent” named ALTER-Math as part of a “design-based research initiative” and observed greater gains among learners as they taught the agent ideas. The “learning-by-teaching” phenomenon is particularly apt for physics, given the importance of expressing reasoning and evaluating assumptions as part of physics problem-solving competence. Taken together, this body of work implies that AI may be a useful guide and cognitive reflection surface—a role encapsulated by this study as part of an upper secondary physics curriculum.

3.4. AI for Assessment and Feedback

Assessment continues to be an important front-end integration opportunity for AI. The FACT model, proposed by Elshall and Badir (2025) (which synthesizes Fundamental, Applied, Conceptual, and critical Thinking) and other approaches, illustrates ways in which AI integration can support rigorous assessment by including the results of AI-mediated assessment approaches. The authors’ results make clear that AI systems, guided by human decision, perform better than unguided AI, and students value AI’s productivity but are wary of reliance. Liu T. et al. (2024) make clear that a large language model approach, like GPT-4, can offer a viable ‘first pass grading strategy’ of mathematical scripts if followed by professional verification, while Bolender et al. (2024) demonstrate associated cost and time savings with ‘customized AI-based pipelines.’

Such evidence aligns with the concerns of physics teachers as identified by Wattanakasiwich et al. (2025), whereby unsupervised AI evaluation could undermine analytical skills. Essentially, the integration between algorithmic evaluation and verification by teachers seems to enhance both the efficient and valid aspects. Within UAE schools, the evaluation reliability and equity as closely watched by education authorities could present a transition between innovation and national quality assurance requirements.

3.5. Inquiry, Cognitive Conflict, and Metacognition

Physics learning may proceed through conceptual conflict and metacognition. Said (2025) shows how generative AI may facilitate productive conceptual conflict in teaching quantum physics by using suggestive or paradoxical statements. Though engagement was significantly enhanced, there was a tendency toward overdependence on AI-based explanations, illustrating the necessity for teacher facilitation. Likewise, ambivalence among teachers toward ChatGPT was identified by Jang and Choi (2025) as being appreciative of its potential to enhance exploration but concerned that critical thinking skills could diminish as a consequence. The development of assessment activities designed to require explanation, evaluation, and transfer instead of recall can produce higher-order critical thinking through AI-based inquiry activities (Tariq, 2025). Taken as a whole, this body of research highlights the critical role that explicit metacognitive support should play when combining the educational potential of AI with physics instruction. Students will need to learn to question the responses given by the AI, make justifiable conclusions, and validate their findings, all principles represented in the instructional approach adopted by the current UAE project.

3.6. Capacity Building, Ethics, and the UAE Context

Teacher training and institutional support influence AI adoption significantly. Massouti et al. (2025) conducted a study among UAE pre-service teachers and found a degree of optimism regarding AI applications in education, although they stressed the importance of AI education and ethics at a curriculum level. Bergdahl and Sjöberg (2025), writing about international trends, remarked that enthusiasm precedes confidence, implying a greater need to move beyond technology training to ethics and education aspects as well. The study by Yehya et al. (2025), exclusively targeting UAE physics teachers, reveals largely favorable opinions, coupled with an unchanged list of training, infrastructure, and workload barriers, all against the UAE national vision requirements related to AI-based education.

The implementation model designed by Schiner (2025) (with schools establishing learning labs involving AI, as well as professional communities) demonstrates viable approaches towards successful implementation. Although originating in the US, the “powerful learning” approach can be applied to technologically advanced school networks, as found in the UAE, enabling physics learning via AI to move beyond pilot projects into national policy-based institutionalized learning environments.

3.7. Interim Summary

Throughout the literature, a number of regularities appear, which relate directly to the justification and conduct of this study. The partnership between AI-based personalization and rapid feedback is repeatedly identified as leading to improved outcomes and self-efficacy, especially among students benefiting from guided facilitation (Castañeda et al., 2024; Hu, 2024; Sung et al., 2024; Xing et al., 2025). Well-structured approaches will, as a further advantage, enhance the quality of instruction by virtue of reduced stress and a sustaining motivational factor (Henze et al., 2024). However, this will require a balanced assessment approach, maintaining a foundation of core analytic skills through human monitoring (Elshall & Badir, 2025; T. Liu et al., 2024). It will require as well a readiness among teachers facilitated by professional preparation and good governance interactions (Bergdahl & Sjöberg, 2025; Dewi PURBA et al., 2025; Wattanakasiwich et al., 2025; Yehya et al., 2025).

However, secondary school physics, as a subject, continues to be inadequately represented in empirical AI studies around the world. The UAE, with its national passion for smart transformation and STEM leadership, offers a unique context to explore how AI-based learning operates effectively in a school setting. Through this classroom-comparative study, as a Grade 11 Physics class receives instruction with AI versus traditional instruction, this research refutes an important gap identified by recent reviews, including the necessity for evidence-based expertise associated with AI features, teaching, and K-12 student performance.

4. Methods

4.1. Research Design

A quasi-experimental pre-test, post-test control group design involving whole classes was adopted to compare the results of AI-based teaching with traditional, classroom-based instruction by teachers, as part of Grade 11 Advanced Physics material. The quasi-experimental design allowed the researchers to conduct a comparison study while maintaining the authenticity of the classroom scenario and restricting disruptions to the normal classroom timetable, as has been advocated by the plethora of school-based AI studies, focusing as they do, on evaluating results amidst an authentic scenario (Kavitha & Joshith, 2024; Moore et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2025).

4.2. Setting and Participants

The study took place in an ATS school in the United Arab Emirates. Two intact Grade 11 Advanced Physics classes participated:

-

Experimental class (boys): received AI-assisted instruction leveraging interactive digital platforms with AI-supported inquiry tools and adaptive feedback routines aligned to the school’s Physics standards.

-

Control class (girls): received traditional teacher-led instruction using textbooks, teacher explanations, and slide-supported lessons.

The intact-class methodology accurately reflects regular class timetables as known in secondary-level schools, in addition to maintaining ecological validity, which is salient as fidelity of program carryout, as well as inter-school coordination, remain paramount issues in relation to technology integration in UAE (Bergdahl & Sjöberg, 2025; Massouti et al., 2025; Yehya et al., 2025).

4.3. Instructional Conditions

Two learning modalities were employed to compare AI-supported and traditional learning environments operating under the same curriculum framework. Under the AI-supported learning mode, classroom instruction was augmented by carefully designed AI-enabled aids incorporated into activities and guided practices. Examples of aids included adaptive suggestions and hints, which were varied according to the response given by users, consistent with the findings by Liu, Z., et al.'s (2024) study, which found that the adaptability inherent in AI applications operating in a K-12 pool dynamically adjusted their content to individual profiles, yielding quality cognitive and affective outcomes among users. Formative feedback, including instant feedback on conceptual and procedural exercises involving kinematic, dynamic, and energy principles, facilitated instant corrections, and AI-enabled inquiry scaffolds further promoted prediction, explanation, and reflection, including activities involving explanations, “compare two solution paths.”

These functions correspond with the roles described in the literature, whereby the AI acts as a teaching assistant, mentor, or coach providing targeted explanations and metacognitive suggestions to support planning and self-monitoring (Castañeda et al., 2024; Dewi PURBA et al., 2025; Xing et al., 2025). Within physics education, the availability of support functions has been demonstrated to enhance motivation and alleviate anxiety while maintaining conceptual accuracy (Henze et al., 2024). Quick explanations further make abstract subject matter, which has often presented a learning difficulty, easier to access (Kotsis, 2024). The teachers included rigorous verification procedures, whereby students were asked to display solution procedures, explain their calculations via diagrammatic explanations, or validate dimensional checks, all reflective of proper strategies to augment AI utilization and retain critical constituting problem-solving faculties (Elshall & Badir, 2025; Said, 2025; Tariq, 2025).

On the other hand, the traditional instruction group was given a traditional classroom structure involving the school curriculum, which included classroom explanations, class demonstrations, exercises involving textbooks, as well as slide presentations. Formative assessment involved class questioning, as well as written exercises, that didn’t make use of any AI feedback or adaptation. The traditional structure offered a basis to compare the influence of AI-based learning on instruction and motivational functions.

4.4. Instruments

Two curriculum-aligned assessments were developed by the school’s Physics department:

-

Pre-test to establish baseline proficiency.

-

Post-test to assess attainment after the instructional period.

The items selected targeted representative items from the Grade 11 Advanced Physics curriculum. The types included multiple-choice, short constructed response, and quantitative problem-solving items. Although the type of tasks was similar between the pre-test and the post-test, the items devised were not exactly alike to prevent any potential practice effect impacts. Reviewing the items involved a two-check procedure among two department teachers to ensure they relate to the relevant curriculum and are clear.

4.5. Procedures

A pre-test was administered to both classes a week before the commencement of instruction. The intervention period included a unit, as per standard class timings. The experimental class relied on AI tools incorporated into lessons, while the control class engaged with related material via conventional activities. The post-test was administered under proctored circumstances at the end of the unit. The teachers kept a record of the coverage reached by each group to guarantee equivalent coverage and any deviations from pacing (none material). There was no extra credit or optional tutorial given to one group but not the other. The teachers kept the purpose of the study secret from students to avoid expectancy effects.

4.6. Data Analysis

Analyses addressed three research questions:

-

RQ1 (mean achievement): Post-test means of the AI-assisted and traditional classes were compared descriptively; baseline comparability was verified from pre-test means.

-

RQ2 (magnitude of difference): Standardized mean difference (Cohen’s d) was computed from post-test results to index practical significance.

-

RQ3 (distribution and consistency): Class-level dispersion and distributional features were examined descriptively and visualized through (a) mean comparison, (b) box plots (median, IQR, and whiskers), and (c) kernel density overlays to inspect spread and potential skew.

Following suggestions proposed by studies researching assessment involving AI (Bolender et al., 2024; Z. Liu et al., 2024), this study highlights the concept of effect size and distribution description rather than focusing solely on hypothesis tests, with visualizations designed to express central tendency and variability as an approach suitable for decision making at a school level.

4.7. Ethical Considerations

The research took place as part of regular classroom instruction, anonymized at a class level, meaning that no personal data was collected or shared. Students followed the typical school curriculum, and the experimental class was exposed to an instruction type that could be supported by the school as well. The teachers were educated on proper AI usage and verification procedures to maintain academic integrity and facilitate a degree of autonomy among students (Elshall & Badir, 2025; Wattanakasiwich et al., 2025).

5. Results

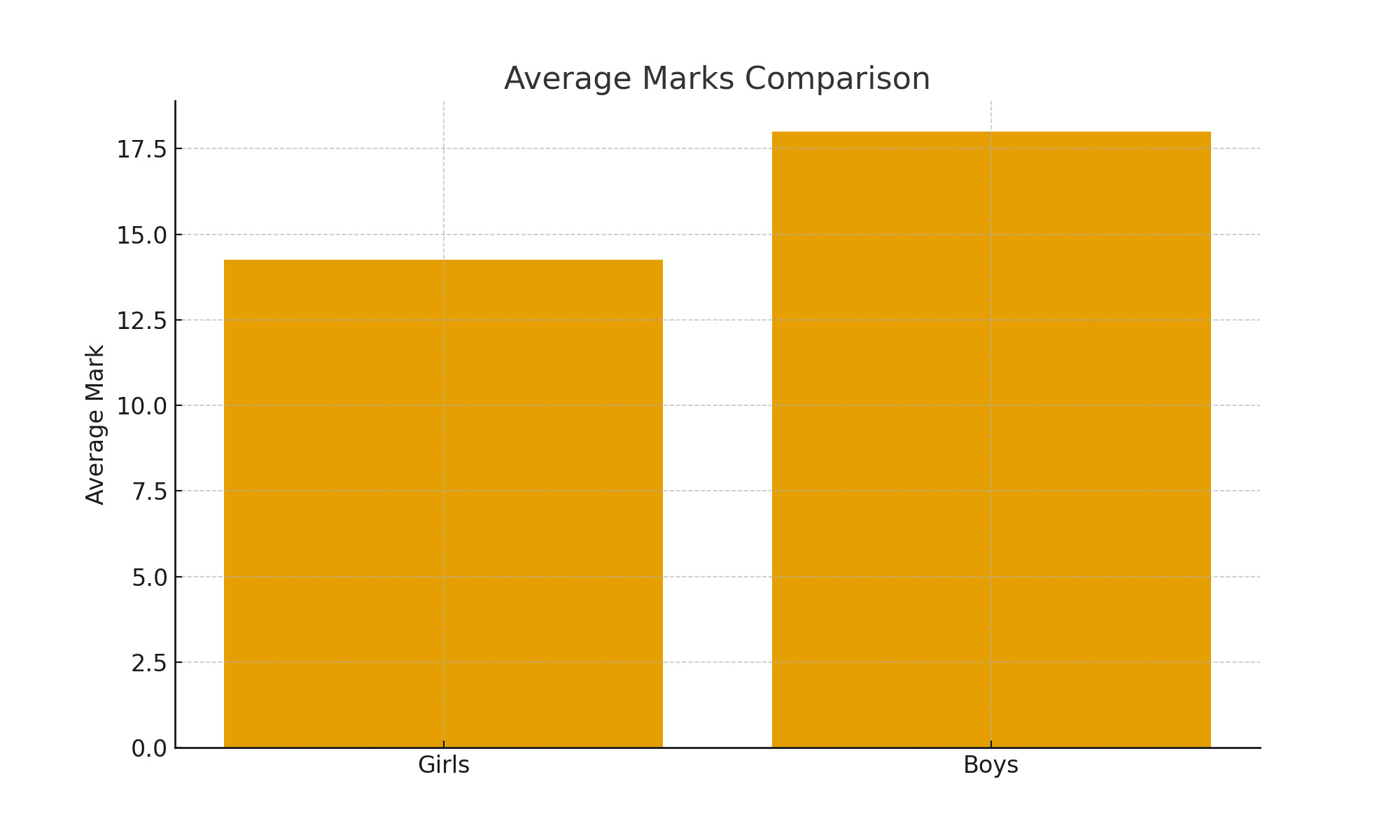

The pre-intervention results showed strong evidence of equivalent baselines between the two intact classes (pre-test means: 72.2% for the AI-assisted class and 71.7% for the traditional class), providing strong internal validity to the results, as commonly practiced in school-based quasi-experiments (see Moore et al., 2022). After the teaching phase, the results of the post-test resulted in favor of the AI-supported class (M = 18.00) over the traditional class (M = 14.25), with a difference of 3.75 scale points, resulting in a large standardized effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.21). On traditional benchmarks, this represents a degree of practical significance with regard to decision-making in a classroom setting, commensurate with meta-analytical evidence regarding the moderate to strong improvement seen with AI-infused personalization, particularly when feedback is rapid and well-targeted to a given skill set or goal (Hu, 2024). The significance and direction seen with this outcome are consistent with findings related to other designs, including AI-infused scaffolding, whether presented as a Teachable Agent or Embedded Assistant, which have been seen to enhance achievement, even when guided by a human educator (Kavitha & Joshith, 2024; Z. Liu et al., 2024; Sung et al., 2024; Xing et al., 2025). The post-test mean difference represented a large effect size (d = 1.21), as seen with other feedback-rich implementations involving AI within STEM environments.

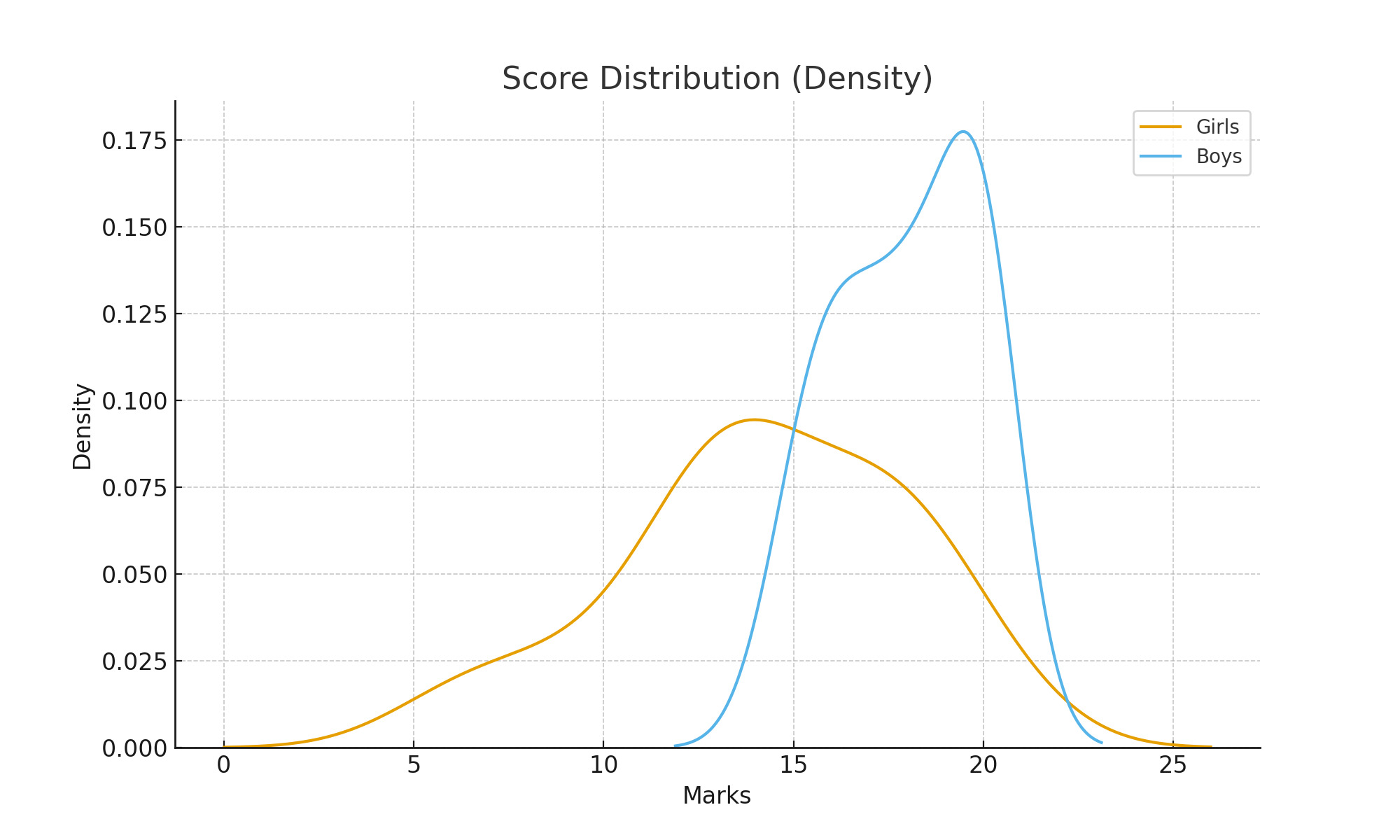

The data distribution-based visualizations validated the existence of significant differences in means (Figures 1, 2, and 3). From the bar/mean graph (Figure 1), a positive displacement reveals an upward displacement in the AI-supported group; from the box graph (Figure 2), an increased central line as well as top lines, denoting decreases in data dispersal, respectively; and finally, from the density graph (Figure 3), an upward displacement, suggesting a lack of weight at the bottom, denotes a scarcity of low-performing data. Such a finding is consistent with evidence that adaptive feedback cycles may enhance learning pathways by detecting mistakes early and providing an opportunity to make corrections, as well as benefiting those learners who require more fine-grained support (Kavitha & Joshith, 2024; Sung et al., 2024). The inherent quality gains often seen with AI-based analysis, including boosts to learner motivation and lower stress levels, may well account for the tighter distribution seen, adding to gains achieved as indicated by the difference detected by the post-test.

The findings appear to validate a number of regularities identified within recent synthesis studies and reviews published within this field. First, when a complementary, rather than replacement, model is envisioned, gains with respect to achievement are prevalent, as has been indicated by various studies (Hu, 2024; Z. Liu et al., 2024; Sung et al., 2024). Second, improvements in central tendency are often contingent upon gains in variability, as indicated by findings related to virtual mentoring and inquiry support initiatives, whereby metacognition statements diminish unaddressed misconceptions over the unit of time represented by the duration of the program (Castañeda et al., 2024; Xing et al., 2025). Third, a potential advantage is predicted by the physics-specific literature for intelligent tutoring, virtual labs, and adaptive technology, although cautions are expressed regarding the role assumptions and utilization by teachers (Al-Kamzari & Alias, 2025; Dewi PURBA et al., 2025; Torralba, n.d.). It should be noted, relative to this broader literature, that a large mean difference with a tighter distribution of scores is consistent with the emerging evidence base as well as providing domain-specific verification in a secondary school population in a Gulf region country.

6. Discussion

The results from the post-test procedure included a large difference in instruction between the AI-based class and the traditional class, with a large effect size measured at 1.21. The degree of the difference measured by the effect size is established as a high-end result among well-aligned AI applications focusing on STEM sectors, signifying an educated difference suitable for a class or school level. The results are suggestive and show a difference between better central tendencies and reduced variability, signifying better uniform performance by the class members, rather than varied results. As both categories of members began the trial with an equal score, this evidence lends well to the strong effectiveness AI-based instruction offers Grade 11 Advanced Physics class members utilizing structured feedback and inquiry-based scaffolding.

The advantage seems to arise through a combination of personalized feedback, inquiry scaffolding, and motivational influences. The availability of adaptive prompting and immediate correction functions enables rapid cycles of improvement and refinement, as described by other accounts noting how AI systems positively influence learning by providing rapid, personalized assistance (Hu, 2024; Kavitha & Joshith, 2024; Z. Liu et al., 2024). Within physics, with its demands for conceptual accuracy and unitary consistency, the availability of feedback functions strengthens problem-solving frameworks and minimizes misunderstanding (Kotsis, 2024; Sung et al., 2024). Hu (2024) measured this advantage of personalization across 31 empirical studies, observing a moderate to strong positive effect scale, consistent with the present findings.

Inquiry scaffolds developed with AI also seemed to facilitate a strong level of metacognitive engagement involving explanation, strategy evaluation, and reflection. The dialogic scaffolding approach replicates past studies incorporating virtual mentoring and Teachable Agent technology, whereby presses toward metacognition promoted greater conceptual development and better self-monitoring accuracy (Castañeda et al., 2024; Xing et al., 2025). However, a greater degree of motivational engagement, as well as lower levels of cognitive stress, as identified as the perks offered by environments augmented by AI technology (Henze et al., 2024), could well account for the reduced variability seen in performance results.

The present trend is consistent with recent integrative meta-analyses. The summary results presented by Zhang et al. (2025) are consistent with STEM education, as they point out the potential value of AI technology integrated into natural classroom environments rather than simulated researches. The results are consistent with large-scale meta-analyses investigating computer science or science education among K-12 populations, as AI technology enhances engagement and achievement when coupled with appropriate teaching methodologies (Kavitha & Joshith, 2024; Z. Liu et al., 2024; Moore et al., 2022). Within physics, the potential outlined by Al-Kamzari and Alias (2025) shares a similar trajectory, although they warn against a mechanistic underestimation of teachers’ adaptability and ethics training related to data handling. The purview outlined by Dewi Purba et al. (2025) and developed further by Torralba (n.d.) contends that the dynamic between teachers and AI should be well-defined to prevent an overlapping ambiguity, a premise demonstrated by this study’s current approach toward guided, rather than self-managed, AI interaction.

A further, crucial aspect, emerging out of the literature, is innovation/assessment rigor: how this is achieved or balanced and how this affects the end results of AI utilization in the classroom. The FACT approach to assessment, outlined by Elshall & Badir (2025)—no-AI activities, AI-infused projects, conceptual tests, critical thinking evaluations—represents a viable solution to this end, as their evidence supporting AI augmented by human oversight as more beneficial than utilizing AI alone fits well with other studies that suggest human verification (Z. Liu et al., 2024), and AI-customized assessment workflows, which can enhance consistency and efficiency (Bolender et al., 2024). Such two-layered grading frameworks involving both AI and human intelligence have been proven applicable in various disciplines related to environmental sciences and mathematics (Elshall & Badir, 2025; T. Liu et al., 2024). Combining derivation by other means, AI-enabled inquiry projects, and concept testing in physics education may retain their rigor while capitalizing on gains.

Teacher competence continues to be the central part of successful implementation processes. The trajectories of technology acceptance show predictable curves involving perceived usefulness, hedonic motives, and institutional promotion as drivers (Wattanakasiwich et al., 2025). Helpful professional development involves rapid design, justifiable reasoning, truth-testing procedures, and type-specific examples (Bergdahl & Sjöberg, 2025; Dewi PURBA et al., 2025; Yehya et al., 2025). Massouti, et al. (2025) further stressed the critical role of providing pre-service and in-service teachers with ethical and technical literacy via integrated multi-tiered initiatives. Within a UAE context, prioritizing strategies aimed at a readiness approach by AI, investments related to learning or classroom development are indeed applicable to the future directions related to responsible integration as done with this study (Massouti et al., 2025; Yehya et al., 2025).

However, gen-AI, with all its merits, carries the potential risks of overdependence and surface-level critical thinking as well. Said (2025) argues that the cognitive conflict facilitated by AI resulted in an increased curiosity drive, but this encouraged students to accept the AI results unquestioningly as well. It is, therefore, crucial to impose metacognitive controls, like marking solution pathways, evaluating other approaches, or explaining the reasoning through diagrams or units, by engaging proper debriefing activities afterwards (Tariq, 2025). Thus, by incorporating critical reflective checkpoints, gen-AI will continue to act as a facilitator, rather than a by passer, of critical thinking.

Finally, whereas environments involving AI could strengthen teaching abilities and allow customized support outside the classroom (Castañeda et al., 2024), a concern with regard to equity implies an interest in both technology and professional communities. The results, including that AI teaching assistants positively affected low-performing students, a subgroup that could likely benefit from additional support, offer persuasive evidence that strategies related to access and maintenance are justified (Sung et al., 2024). Innovations developed at this school level, whether related to building learning labs or communities of practice, including applications involving AI, offer viable approaches to scale up while maintaining equity and instruction (Schiner, 2025).

Such themes convey a vision of AI-augmented education as a evolution, not a innovation, a development essentially rooted in feedback, metacognition, and proper assessment rather than just a mere technological innovation. The resultant improvement noted in Grade 11 Physics, therefore, illustrates how AI as a tool incorporated into a reflective and guided approach can augment, rather than replace, teaching functions.

7. Limitations and Pedagogical Implications

Although the results of this study offer robust evidence for the instructionally viable role of AI-supported learning in physics, a number of features related to methodology and context limit the generalizability of the findings. First, the quasi-experimental approach involved intact groups, leading to potential concerns regarding extraneous variables including class dynamics and gender representation. The study could have faced biases due to the differing interaction patterns, motivational, or strategical approaches between the groups, as the treatment group included boys and the control groups included girls, respectively. Randomized experiments involving mixed-gender enrollments or gender effect controls should be incorporated into future studies to better tease out the instructionally related contributions of AI-based support. The study was limited to two classes in a school, enabling consistent delivery, but restricting generalizability to other schools and grade levels could enable an exploration of whether the measured advantage for AI-supported instruction generalizes to other populations as well.

Second, the results are limited by their focus on a short-term measurement scale. The post-test measured the immediate gains, but this did not evaluate how this learning is retained or the motivational levels, as suggested by Zhang et al. (2025) and Kavitha and Joshith (2024), as tracing how the gains achieved are transformed into a learning trajectory is paramount. Furthermore, this assessment is confined to a quantitative approach, which, as discussed, is strict but provides little clarity or information with regard to how the students are engaged with the facilitated interaction by AI technology. Adding a component involving reflective journaling, dialogical transcripts, or classroom observations, as proposed by Dewi Purba et al. in 2025 and Castañeda et al. in 2024, respectively, may allow greater clarity with regard to how the students are coping with inquiry activities or how they are utilizing feedback or reasoning strategies, respectively. Additionally, this AI-enabled learning environment was implemented with the supports and directions given by teachers, both as a result of a localized approach. Differences may occur due to the variability in tools, teachers’ capabilities, or foundational technological frameworks, so as to make a significantly greater or differing impact upon the learning gains (Bergdahl & Sjöberg, 2025; Yehya et al., 2025).

Despite this, the results are directly applicable to instruction, instruction development, or assessment as well. It is clear that environments augmented by AI are capable, as a significantly positive impact on both levels and accuracy, of raising physics at the secondary level when designed with an inquiry scaffold and feedback system. The significance of this construct is well supported by various other studies as well (Henze et al., 2024; Hu, 2024). As a matter of approach, physics teachers can make use of AI systems as collaboration tools that supplement classroom learning rather than replacing classroom instruction, acting as reactive tutors that can identify misgivings and pace learning accordingly. Reflective questioning integrated into AI interactions (Said, 2025; Tariq, 2025), will assist students in justifying their decisions, evaluating competing results, and checking results produced by an AI system, hence strengthening critical and metacognition skills.

However, in order to ensure the long-term effectiveness of all these advantages, teachers should be exposed to a comprehensive professional development program, moving beyond a mere technical expertise approach. As pointed out by previous studies (c.f. Bergdahl & Sjöberg, 2025), enthusiasm levels are significantly greater than confidence levels related to AI integration, leading to a substantial gap that does not fully support quality integration, hence the training program should encompass both expertise and critical insights. Wattanakasiwich et al. (2025) and Massouti et al. (2025) further emphasize that confidence and competence, rather than willingness, are the key barriers to integration. The creation of professional development modules regarding AI literacy, prompt engineering, and reflective supervision, among others, will prepare teachers to effectively incorporate AI into physics instruction.

Lastly, this research emphasizes the importance of assessment reform to accommodate novel trends that are emerging as realities in instruction. The FACT approach to assessment (Elshall & Badir, 2025) offers a rounded approach whereby the essential ‘no AI tasks’ are integrated with applications, conceptual analysis, and critical-thinking activities. The semi-automated approach to grading, confirmed by human evaluators (Z. Liu et al., 2024), coupled with generative item development useful for formative assessment (Bolender et al., 2024), will enhance accuracy, productivity, and immediacy while making physics a more adaptative, exploratory, and cognitively engaging enterprise as a learning process with the infusion of AI applications, if reflective pedagogy is adequately incorporated into how physics teachers are prepared as professionals.

8. Conclusion

AI-enabled learning is a major teaching innovation in physics education offered at the secondary school level. The inclusion of adaptive AI systems in a UAE ATS school resulted in a substantial achievement gain and relatively consistent levels of performance compared to traditional instruction, with a large effect size of 1.21. Such results are consistent with international evidence establishing the efficacy of AI to improve or enhance personalization, engagement, and inquiry approaches (Castañeda et al., 2024; Henze et al., 2024; Hu, 2024; Kavitha & Joshith, 2024).

Although very promising, scaling up necessarily involves rigorous assessment development, professional development, and a strong set of ethics. A well-rounded approach integrating inquiry via AI, coupled with teachers’ reflective analysis and verification, will assure innovation as well as academic integrity. Such findings are supported by the meta-analytical evidence presented by Hu (2024) and reviews presented by Liu, Z., et al. (2024) and ultimately supported by reviews by Al-Kamzari and Alias (2025), all converging to validate AI’s visible, transferable gains related to personalized engagement activities in STEM education. When effectively incorporated into a country’s vision, like the UAE, AI-powered learning will have the potential to be at the foundation of a future-proof STEM education system, teachers included, bolstering conceptual development and cultivating a lifelong passion to inquire into science.

Conflict of Interest / Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing or conflicting interests.

Acknowledgments

None.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated.

Ethics Approval and Consent

In line with institutional norms for minimal-risk educational evaluations, this study analyzed anonymized data derived from routine classroom instruction conducted as part of the regular school curriculum. No procedures beyond standard educational practice were introduced, and students’ grades or academic standing were not affected. No identifying information was collected.

AI Tool Use Disclosure

AI tool: ChatGPT. Provider: OpenAI. Version: GPT-5, Nov. 2025. Purpose: Language editing. Verification: The authors reviewed and verified all output.

Preprint Disclosure

This article has not appeared as a preprint anywhere.

Third-Party Material Permissions

No third-party material requiring permission has been used.

._the_ai-assisted_class_exhibits_a_higher_median_and_upper_qu.png)

._the_ai-assisted_class_exhibits_a_higher_median_and_upper_qu.png)