Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is a common and clinically important condition characterized by inflammation of pancreatic tissue and associated with substantial morbidity and mortality (Wang et al., 2009). The predominant etiologies are gallstones and alcohol—together responsible for roughly 70–80% of cases—followed by hypertriglyceridemia as the third most common cause (Sakorafas & Tsiotou, 2000; Yang & McNabb-Baltar, 2020). Procedure-related pancreatitis also occurs after instrumentation of the pancreaticobiliary system, most notably endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (Cotton et al., 2009; Freeman & Guda, 2004). By contrast, pancreatitis temporally following esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)—a procedure widely used for diagnostic and therapeutic upper gastrointestinal indications—is rare and has been reported only in scattered case reports and abstracts over more than four decades (Dai et al., 2022; Deschamps et al., 1982; Fadaee & De Clercq, 2019; Gaddameedi et al., 2024; Jacob et al., 2024; Mirchev et al., 2020; Modi et al., 2023; Nevins & Keeffe, 2002; Nwafo, 2017; Oshima et al., 2022; Sturlis & McGrane, 2022).

Diagnosis is established using the current ACG guidelines, which require at least two of the following: (1) characteristic abdominal pain; (2) serum lipase or amylase ≥3× the upper limit of normal; and/or (3) imaging findings consistent with acute pancreatitis (Banks et al., 2013; Tenner et al., 2024).

Acute pancreatitis results in approximately 200,000–275,000 U.S. hospitalizations annually; approximately 80% of presentations are mild and self-limited, whereas overall mortality is ~1–2% (Forsmark et al., 2016; Mohy-ud-din & Morrissey, 2023). When evaluating a patient presenting with acute pancreatitis it is important to identify the underlying cause in order to avoid further injury or direct diagnostic and therapeutic measures. Accordingly, clinicians should assess for recent procedures as potential iatrogenic triggers, even when manipulation of the ampulla or ducts has not occurred (Wang et al., 2009; Yang & McNabb-Baltar, 2020).

ERCP is indispensable for managing choledocholithiasis, biliary strictures, and cholangitis, but post-ERCP pancreatitis is a recognized adverse event, occurring in roughly 2 – 40% of patients undergoing ERCP (Cotton et al., 2009; Turner et al., 2012).

EGD is a widely used, minimally invasive procedure for upper gastrointestinal indications. Interventions during EGD may include hemostasis, mucosal resection (e.g., EMR), dilation, and biopsy. It is generally considered safe, with very low complication rates for diagnostic EGD and mortality on the order of ~0.004% in historical series, though risks rise with therapeutic maneuvers (Dunkin, 2006; Palmer, 2007; Wolfsen et al., 2004). Nevertheless, pancreatitis after EGD has been documented, particularly in settings involving duodenal interventions near the ampullary region (Dai et al., 2022; Fadaee & De Clercq, 2019; Gaddameedi et al., 2024; Kwak et al., 2009; Mirchev et al., 2020; Modi et al., 2023; Oshima et al., 2022).

Proposed mechanisms include papillary edema or transient obstruction after biopsy, thermal or inflammatory injury from endoscopic mucosal resection/polypectomy, and duodenal overdistension/insufflation effects—mechanisms that are biologically plausible despite the rarity of the event (Deschamps et al., 1982; Fadaee & De Clercq, 2019; Kwak et al., 2009; Mirchev et al., 2020; Modi et al., 2023).

Against this background, we report a case of acute interstitial pancreatitis developing within hours of a routine surveillance EGD with duodenal biopsy and provide an updated review of published cases (13 in total) to contextualize incidence, timing, putative mechanisms, clinical features, and outcomes of this uncommon complication.

Case Presentation

A 42-year-old man with genetically confirmed Lynch syndrome underwent a routine surveillance EGD, having had a colonoscopy two weeks earlier that revealed a non-neoplastic polyp. The procedure was uneventful except for a biopsy from a small mucosal prominence in the second portion of the duodenum (D2). He was discharged home in good condition but returned to the emergency department six hours later with sudden, severe epigastric pain radiating to the back and associated nausea.

On examination, his vital signs were: heart rate 104 bpm, respiratory rate 16 breaths/min, SpO₂ 99%, temperature 37.3 °C, and blood pressure 133/90 mmHg. He appeared uncomfortable but was hemodynamically stable. Abdominal examination revealed localized epigastric tenderness without guarding, rebound, or other peritoneal signs. Laboratory studies showed a lipase level more than three times the upper limit of normal, while liver function tests remained within the reference range throughout admission. Serum calcium and triglyceride levels were also normal, and the patient denied alcohol intake or the use of prescription, herbal, or over-the-counter medications.

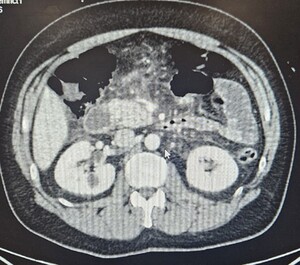

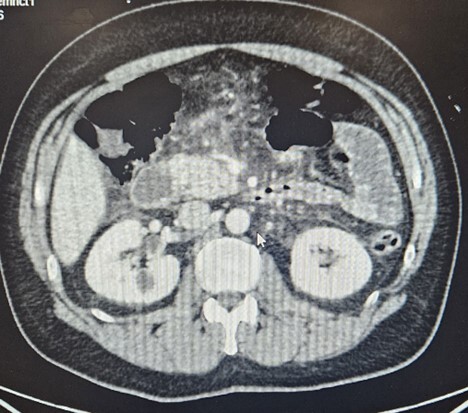

A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated acute interstitial edematous pancreatitis without biliary dilatation, necrosis, or peripancreatic fluid collections (Figure 1).

The patient was admitted, and initiated on supportive management. He received intravenous fluid resuscitation with Ringer’s lactate, guided by hemodynamic parameters and urine output. Oral intake was resumed early, with liquids advanced to a full diet within 24 hours as tolerated. Analgesics and antiemetics were administered for symptom control.

His clinical course was uncomplicated. Abdominal pain gradually improved, and he was able to tolerate a regular diet by the fourth day. He was discharged home in excellent condition, with complete resolution of symptoms and no further complications.

Discussion

Acute pancreatitis following routine EGD is a rare but potentially serious complication. While pancreatitis is a well-documented adverse event of ERCP, its occurrence following diagnostic EGD (with or without limited therapeutic maneuvers and without ampullary cannulation) is exceedingly rare. Published evidence remains confined to case reports and conference abstracts spanning over four decades, totaling 13 prior cases plus our own (Ahmad et al., 2018; Dai et al., 2022; Deschamps et al., 1982; Fadaee & De Clercq, 2019; Gaddameedi et al., 2024; Jacob et al., 2024; Kwak et al., 2009; Mirchev et al., 2020; Modi et al., 2023; Nevins & Keeffe, 2002; Nwafo, 2017; Oshima et al., 2022; Sturlis & McGrane, 2022).

Limited case reports and evidence suggest a potential causal relationship between EGD and acute pancreatitis. Mechanistic explanations proposed include periampullary edema or transient papillary obstruction after duodenal biopsy, thermal or inflammatory injury following mucosal resection or polypectomy, and duodenal overdistension with insufflation leading to retrograde flow into the pancreatic duct (Dai et al., 2022; Fadaee & De Clercq, 2019; Kwak et al., 2009; Mirchev et al., 2020; Oshima et al., 2022). In rare instances, pancreatitis has been documented even when serum lipase was normal, underscoring the need to integrate clinical findings and imaging into diagnostic reasoning (Sturlis & McGrane, 2022).

Through a comprehensive review, we identified 13 published cases of post-EGD pancreatitis between 1982 and 2024, in addition to our own (n = 14). When viewed collectively, these reports reveal consistent temporal association with EGD, careful exclusion of common etiologies, and a disproportionate clustering around duodenal interventions, particularly those performed in the second portion of the duodenum (Ahmad et al., 2018; Dai et al., 2022; Deschamps et al., 1982; Fadaee & De Clercq, 2019; Gaddameedi et al., 2024; Jacob et al., 2024; Kwak et al., 2009; Mirchev et al., 2020; Modi et al., 2023; Nevins & Keeffe, 2002; Nwafo, 2017; Oshima et al., 2022; Sturlis & McGrane, 2022). Although causality cannot be proven, the combination of temporality, biological plausibility, and lack of alternative explanations provides compelling circumstantial evidence.

In terms of demographics, the 13 published cases demonstrated an equal distribution between males and females, with 7 males (50%) and 7 females (50%), and an age range of 33 to 86 years (mean 54.3 years).

The median time to symptom onset was 4 hours (range 2–18), consistent with our patient’s presentation at 6 hours. This narrow latency window is striking, with nearly all reports describing pain within hours of duodenal biopsy, mucosal resection, or even diagnostic procedures without direct papillary manipulation (Dai et al., 2022; Fadaee & De Clercq, 2019; Gaddameedi et al., 2024; Mirchev et al., 2020; Oshima et al., 2022). Clinically, this underscores the importance of vigilance for severe epigastric pain developing during the first post procedural day.

Duodenal interventions accounted for 50% of reported cases (7 of 14) and appeared to carry a higher risk of complications compared with purely diagnostic procedures. Among these, the most severe outcome was a fatal necrotizing pancreatitis following duodenal polypectomy (Kwak et al., 2009).

Treatment across cases has consistently focused on supportive measures. Guideline-based management emphasizes judicious, goal-directed intravenous hydration with isotonic crystalloids, avoidance of prophylactic antibiotics in sterile pancreatitis, and early initiation of oral or enteral feeding in mild cases (Greenberg et al., 2016; Tenner et al., 2024). In this context, the uncomplicated and relatively short clinical course observed in our patient mirrors the outcomes reported in most prior cases.

Length of hospital stay in published cases (n = 14) varied widely, ranging from 3 to 62 days (Table 3). Poorer outcomes—including one survival with complications and one death—were more common in patients undergoing duodenal interventions and in those who developed necrotizing pancreatitis. Traditional risk factors for pancreatitis, including gallstones, alcohol use, and hypertriglyceridemia, were absent in nearly all reported cases. This reinforces the likelihood of a procedure-related etiology, particularly when symptom onset was rapid and alternative causes were excluded by imaging and laboratory studies (Dai et al., 2022; Gaddameedi et al., 2024; Oshima et al., 2022).

From a methodological perspective, caution is warranted. The available evidence is almost exclusively limited to case reports and conference abstracts, which are subject to incomplete reporting, heterogeneity in diagnostic evaluation, and publication bias. Furthermore, because diagnostic EGD carries an overall complication rate well below 2%—as supported by ASGE expert consensus—and pancreatitis is extraordinarily uncommon within that spectrum, aggregated case counts are insufficient for estimating true risk, and causality remains inferential rather than proven (ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, 2012; trainee vs attending complication data suggests ≈0.2% overall rate).

Finally, for clinical practice, comparison with post-ERCP pancreatitis provides useful context. Post-ERCP pancreatitis occurs in approximately 2 - 40% of patients undergoing ERCP, whereas pancreatitis after diagnostic EGD remains an outlier event (Cotton et al., 2009; Tenner et al., 2024). Nevertheless, awareness is crucial: developing epigastric pain within hours of EGD—especially after duodenal interventions—should prompt timely evaluation with pancreatic enzymes and selective imaging, enabling early recognition and supportive management.

Limitations

This review is limited by the nature of available evidence, which consists almost exclusively of single case reports and conference abstracts. Such reports often lack complete laboratory, imaging, or follow-up data, and are subject to publication bias, as rare or severe cases are more likely to be published. Variability in procedural details, diagnostic thresholds, and management approaches across reports further limits direct comparison. Finally, because the incidence of pancreatitis after EGD is extraordinarily low, aggregated case counts cannot be used to estimate true risk, and causality remains inferential rather than proven.

Conclusion

This case adds to the limited but growing body of literature on post-EGD pancreatitis and highlights the importance of considering this diagnosis in patients presenting with abdominal pain after EGD, particularly following procedures involving duodenal intervention. Although exceedingly rare, the consistency of prior reports underscores that clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion when severe epigastric pain develops within hours of the procedure.

Extra caution is warranted when performing EMR, biopsy, or other interventions near the ampulla of Vater, where even limited trauma or edema may precipitate acute pancreatitis. Incorporating this awareness into procedural planning and post-procedure monitoring could facilitate earlier recognition.

Ultimately, recognition of this complication has both clinical and educational value: it contributes to informed consent discussions, guides careful post-procedure assessment of abdominal pain, and enriches the broader understanding of iatrogenic pancreatitis outside the context of ERCP. Ongoing systematic reporting of such cases will be essential to clarify mechanisms, refine risk stratification, and inform preventive strategies.

Clinical Implications

-

Acute pancreatitis after routine EGD is extremely rare but documented. Awareness is important when evaluating post-procedural abdominal pain.

-

Symptom onset is typically within hours of the procedure (median ~4 hours, range 2–18).

-

Duodenal interventions (biopsy, EMR, polypectomy, hemostasis near the ampulla) are disproportionately represented among reported cases and may carry higher risk.

-

Diagnosis relies on the ACG guidelines with characteristic abdominal pain, serum enzyme elevation, and supportive imaging.

-

Management should follow standard guidelines for acute pancreatitis: goal-directed IV fluids , early refeeding as tolerated, and avoidance of prophylactic antibiotics in sterile disease.

-

Implications for practice: include this risk in consent discussions, monitor carefully for new epigastric pain after duodenal interventions, and evaluate promptly with enzymes and imaging if suspected.

Conflict of Interest / Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing or conflicting interests.

Acknowledgments

None.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval and Consent

No ethical board approval was required, as all data were anonymized.

AI Tool Use Disclosure

AI tool: ChatGPT. Provider: OpenAI. Version: GPT-5, August 2025. Purpose: Language editing. Verification: All outputs were reviewed by the authors.

Preprint Disclosure

This article has not appeared as a preprint anywhere.

Third-Party Material Permissions

No third-party material requiring permission has been used.